There are anti-phishing websites which publish exact messages that have been recently circulating the internet, such as FraudWatch International and Millersmiles. Such sites often provide specific details about the particular messages.

As recently as 2007, the adoption of anti-phishing strategies by businesses needing to protect personal and financial information was low. Now there are several different techniques to combat phishing, including legislation and technology created specifically to protect against phishing. These techniques include steps that can be taken by individuals, as well as by organizations. Phone, web site, and email phishing can now be reported to authorities, as described below.

User training

People can be trained to recognize phishing attempts, and to deal with them through a variety of approaches. Such education can be effective, especially where training emphasises conceptual knowledge and provides direct feedback.

Many organisations run regular simulated phishing campaigns targeting their staff to measure the effectiveness of their training.

People can take steps to avoid phishing attempts by slightly modifying their browsing habits.When contacted about an account needing to be "verified" (or any other topic used by phishers), it is a sensible precaution to contact the company from which the email apparently originates to check that the email is legitimate. Alternatively, the address that the individual knows is the company's genuine website can be typed into the address bar of the browser, rather than trusting any hyperlinks in the suspected phishing message.

Nearly all legitimate e-mail messages from companies to their customers contain an item of information that is not readily available to phishers. Some companies, for example PayPal, always address their customers by their username in emails, so if an email addresses the recipient in a generic fashion ("Dear PayPal customer") it is likely to be an attempt at phishing. Furthermore, PayPal offers various methods to determine spoof emails and advises users to forward suspicious emails to their spoof@PayPal.com domain to investigate and warn other customers. However it is unsafe to assume that the presence of personal information alone guarantees that a message is legitimate, and some studies have shown that the presence of personal information does not significantly affect the success rate of phishing attacks; which suggests that most people do not pay attention to such details.

Emails from banks and credit card companies often include partial account numbers. However, recent research has shown that the public do not typically distinguish between the first few digits and the last few digits of an account number—a significant problem since the first few digits are often the same for all clients of a financial institution.

The Anti-Phishing Working Group produces regular report on trends in phishing attacks.

Google posted a video demonstrating how to identify and protect yourself from Phishing scams.

Technical approaches

A wide range of technical approaches are available to prevent phishing attacks reaching users or to prevent them from successfully capturing sensitive information.

Filtering out phishing mail

Specialized spam filters can reduce the number of phishing emails that reach their addressees' inboxes. These filters use a number of techniques including machine learning and natural language processing approaches to classify phishing emails, and reject email with forged addresses.

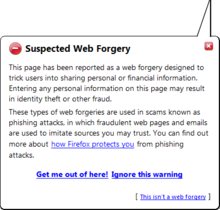

Browsers alerting users to fraudulent websites

Another popular approach to fighting phishing is to maintain a list of known phishing sites and to check websites against the list. One such service is the Safe Browsing service.[140] Web browsers such as Google Chrome, Internet Explorer 7, Mozilla Firefox 2.0, Safari 3.2, and Opera all contain this type of anti-phishing measure.Firefox 2 used Google anti-phishing software. Opera 9.1 uses live blacklists from Phishtank, cyscon and GeoTrust, as well as live whitelists from GeoTrust. Some implementations of this approach send the visited URLs to a central service to be checked, which has raised concerns about privacy. According to a report by Mozilla in late 2006, Firefox 2 was found to be more effective than Internet Explorer 7 at detecting fraudulent sites in a study by an independent software testing company.

An approach introduced in mid-2006 involves switching to a special DNS service that filters out known phishing domains: this will work with any browser, and is similar in principle to using a hosts file to block web adverts.

To mitigate the problem of phishing sites impersonating a victim site by embedding its images (such as logos), several site owners have altered the images to send a message to the visitor that a site may be fraudulent. The image may be moved to a new filename and the original permanently replaced, or a server can detect that the image was not requested as part of normal browsing, and instead send a warning image.

Augmenting password logins

The Bank of America website is one of several that asks users to select a personal image (marketed as SiteKey) and displays this user-selected image with any forms that request a password. Users of the bank's online services are instructed to enter a password only when they see the image they selected. However, several studies suggest that few users refrain from entering their passwords when images are absent. In addition, this feature (like other forms of two-factor authentication) is susceptible to other attacks, such as those suffered by Scandinavian bank Nordea in late 2005, and Citibank in 2006.

A similar system, in which an automatically generated "Identity Cue" consisting of a colored word within a colored box is displayed to each website user, is in use at other financial institutions.

Security skins are a related technique that involves overlaying a user-selected image onto the login form as a visual cue that the form is legitimate. Unlike the website-based image schemes, however, the image itself is shared only between the user and the browser, and not between the user and the website. The scheme also relies on a mutual authentication protocol, which makes it less vulnerable to attacks that affect user-only authentication schemes.

Still another technique relies on a dynamic grid of images that is different for each login attempt. The user must identify the pictures that fit their pre-chosen categories (such as dogs, cars and flowers). Only after they have correctly identified the pictures that fit their categories are they allowed to enter their alphanumeric password to complete the login. Unlike the static images used on the Bank of America website, a dynamic image-based authentication method creates a one-time passcode for the login, requires active participation from the user, and is very difficult for a phishing website to correctly replicate because it would need to display a different grid of randomly generated images that includes the user's secret categories.

Monitoring and takedown

Several companies offer banks and other organizations likely to suffer from phishing scams round-the-clock services to monitor, analyze and assist in shutting down phishing websites. Individuals can contribute by reporting phishing to both volunteer and industry groups, such as cyscon or PhishTank. Individuals can also contribute by reporting phone phishing attempts to Phone Phishing, Federal Trade Commission. Phishing web pages and emails can be reported to Google. The Internet Crime Complaint Center noticeboard carries phishing and ransomware alerts.

Transaction verification and signing

Solutions have also emerged using the mobile phone (smartphone) as a second channel for verification and authorization of banking transactions.

Multi-factor authentication

Organisations can implement two factor or multi-factor authentication (MFA), which requires a user to use at least 2 factors when logging in. (For example, a user must both present a smart card and a password). This mitigates some risk, in the event of a successful phishing attack, the stolen password on its own cannot be reused to further breach the protected system. However, there are several attack methods which can defeat many of the typical systems. MFA schemes such as WebAuthn address this issue by design.

Email content redaction

Organizations that prioritize security over convenience can require users of its computers to use an email client that redacts URLs from email messages, thus making it impossible for the reader of the email to click on a link, or even copy a URL. While this may result in an inconvenience, it does almost completely eliminate email phishing attacks.

Limitations of technical responses

An article in Forbes in August 2014 argues that the reason phishing problems persist even after a decade of anti-phishing technologies being sold is that phishing is "a technological medium to exploit human weaknesses" and that technology cannot fully compensate for human weaknesses.

Legal responses

On January 26, 2004, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission filed the first lawsuit against a suspected phisher. The defendant, a Californian teenager, allegedly created a webpage designed to look like the America Online website, and used it to steal credit card information. Other countries have followed this lead by tracing and arresting phishers. A phishing kingpin, Valdir Paulo de Almeida, was arrested in Brazil for leading one of the largest phishing crime rings, which in two years stole between US$18 million and US$37 million. UK authorities jailed two men in June 2005 for their role in a phishing scam, in a case connected to the U.S. Secret Service Operation Firewall, which targeted notorious "carder" websites. In 2006 eight people were arrested by Japanese police on suspicion of phishing fraud by creating bogus Yahoo Japan Web sites, netting themselves ¥100 million (US$870,000). The arrests continued in 2006 with the FBI Operation Cardkeeper detaining a gang of sixteen in the U.S. and Europe.

In the United States, Senator Patrick Leahy introduced the Anti-Phishing Act of 2005 in Congress on March 1, 2005. This bill, if it had been enacted into law, would have subjected criminals who created fake web sites and sent bogus emails in order to defraud consumers to fines of up to US$250,000 and prison terms of up to five years.The UK strengthened its legal arsenal against phishing with the Fraud Act 2006, which introduces a general offence of fraud that can carry up to a ten-year prison sentence, and prohibits the development or possession of phishing kits with intent to commit fraud.

Companies have also joined the effort to crack down on phishing. On March 31, 2005, Microsoft filed 117 federal lawsuits in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Washington. The lawsuits accuse "John Doe" defendants of obtaining passwords and confidential information. March 2005 also saw a partnership between Microsoft and the Australian government teaching law enforcement officials how to combat various cyber crimes, including phishing. Microsoft announced a planned further 100 lawsuits outside the U.S. in March 2006, followed by the commencement, as of November 2006, of 129 lawsuits mixing criminal and civil actions. AOL reinforced its efforts against phishing in early 2006 with three lawsuits seeking a total of US$18 million under the 2005 amendments to the Virginia Computer Crimes Act,and Earthlink has joined in by helping to identify six men subsequently charged with phishing fraud in Connecticut.

In January 2007, Jeffrey Brett Goodin of California became the first defendant convicted by a jury under the provisions of the CAN-SPAM Act of 2003. He was found guilty of sending thousands of emails to America Online users, while posing as AOL's billing department, which prompted customers to submit personal and credit card information. Facing a possible 101 years in prison for the CAN-SPAM violation and ten other counts including wire fraud, the unauthorized use of credit cards, and the misuse of AOL's trademark, he was sentenced to serve 70 months. Goodin had been in custody since failing to appear for an earlier court hearing and began serving his prison term immediately.